The Annual Illinois Chartbook: How Do Taxes in Illinois Compare to Other States?

The Annual Illinois Chartbook:

How Do Taxes in Illinois Compare to Other States?

fffffffff

February 2026 (79.1)

Executive Summary

Illinois state and local tax collections remained higher than the national average in State Fiscal Year 2023, according to an annual analysis by the Taxpayers’ Federation of Illinois (TFI). Illinois and its local governments continue to carry substantial debt, largely the result of decades-long underfunding of public pension systems that allowed governments to finance ongoing spending without commensurate increases in revenue.

This annual analysis of state and local taxes is prepared for policymakers seeking an objective view of Illinois’ tax landscape and how it compares with other states.

About this Chartbook

States differ in how they finance public services, with some relying more heavily on state-level taxes, while others depend more on local taxes. For instance, when a consumer pays sales tax on a retail purchase, the actual government imposing or receiving the tax is typically of little consequence to the consumer. To account for these state-by-state variations, this report relies on combined state and local tax data available through the U.S. Census Bureau, specifically, the Annual Survey of State and Local Finances. While this assures an accurate and comprehensive intergovernmental comparison, it also means the most recent data available is for the fiscal year that started July 1, 2022 and ended June 30, 2023 (Illinois State Fiscal Year 2023).

Comparing taxes based solely on the dollar amount of taxes paid can be misleading. Higher tax collections or payments may simply reflect higher average incomes rather than a heavier effective tax burden. Focusing only on dollar amounts therefore risks overstating relative tax burdens and obscuring how much of a state’s economic activity is actually devoted to taxes. To account for these economic factors, TFI measures taxes as a percentage of Gross State Product (GSP) – the total value of goods and services produced within a state. Expressing taxes relative to GSP provides a more clear view of how much economic activity is devoted to taxation and avoids distortions caused by differences in population size or inflation.

Census data has its limitations, but it is the most comprehensive data source available. Gross receipt taxes, such as Washington State’s Business and Operations Tax or Texas’ Margin Tax, are often a replacement for a corporate income tax. However, the U.S. Census includes gross receipt taxes with sales and excise taxes. There are other instances where the Census guidelines and classifications may not be intuitive, but for simplicity and consistency, we follow the Census classifications.

Past editions of this Chartbook separated individual and corporate income tax collections, but that approach is less meaningful as states adopt pass-through entity taxes (“PTET”). As the Tax Policy Center has noted, states differ in how they classify these revenues: some treat PTET payments as part of the individual income tax, others report them under the corporate income tax, and a few split them between the two. Because PTET can shift revenue across these categories even when the underlying economic activity is unchanged, TFI will now review individual and corporate income tax collections together to provide a clearer picture of total income-based tax receipts. This approach improves comparability, but it masks important differences in how taxes are distributed between business entities and individual taxpayers.

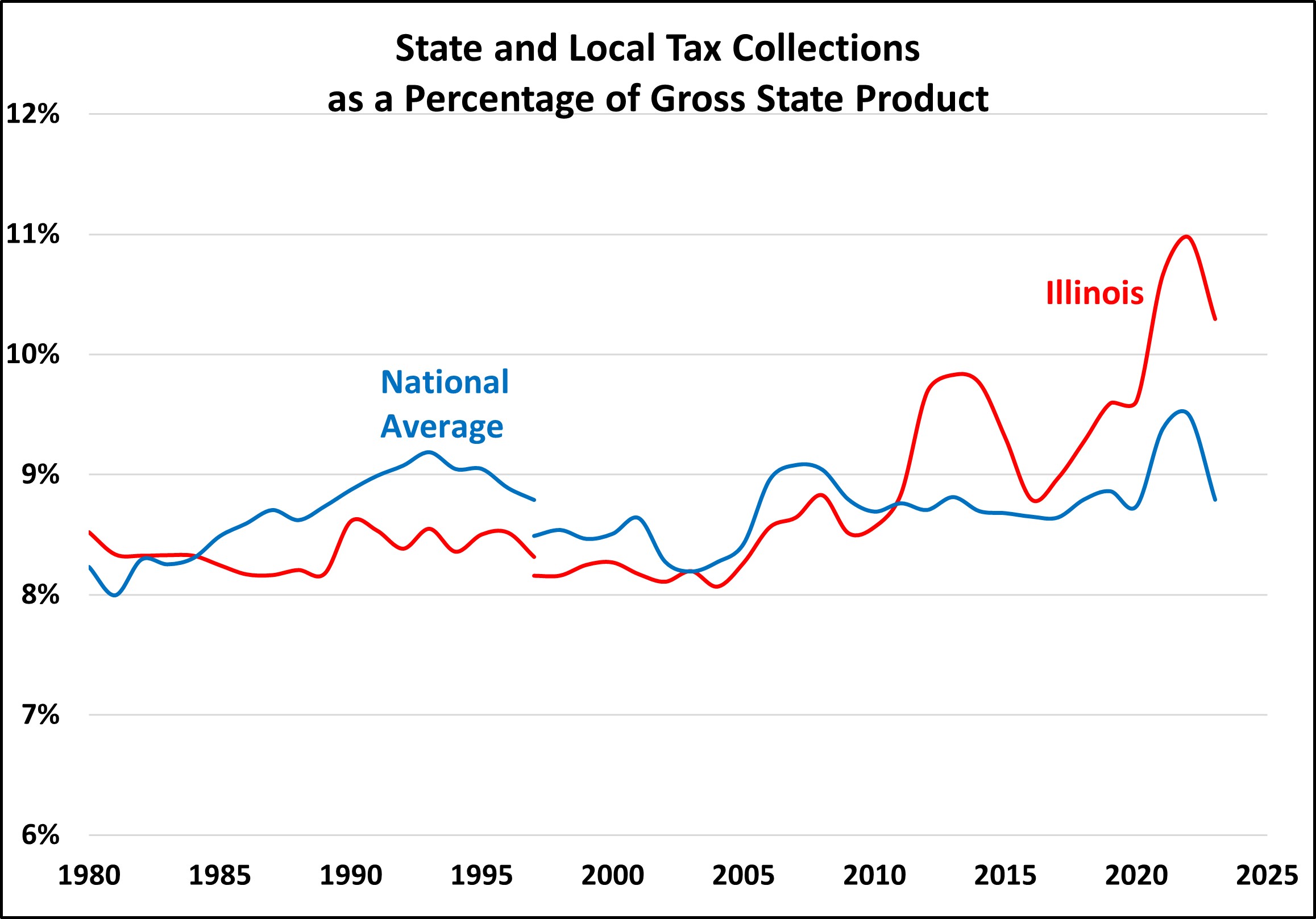

ILLINOIS CONTINUES TO SEE HIGHER TAXES OVER HISTORICAL AVERAGES

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Illinois’ tax collections have continued to increase in recent years. Before 2010, Illinois’ total state and local tax collections as a percentage of GSP were slightly below the national average. However, Illinois started to be significantly higher than the national average due to the significant changes to incomes taxes in 2011, 2015, and 2017. The divergence seems to be increasing, possibly because a large number of states have been reducing taxes while Illinois has not. Total state and local taxes in Illinois in SFY2023 increased by 0.8% in nominal dollars, but Illinois’ GSP increased nominally by 7.5%. This combination resulted in the decline in state and local taxes as a percentage of GSP.

In 1997, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis changed how gross domestic product and GSP were calculated, resulting in slightly higher values. The U.S. Census Bureau did not perform the Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances in 2001 and 2003, so data is unavailable for those years.

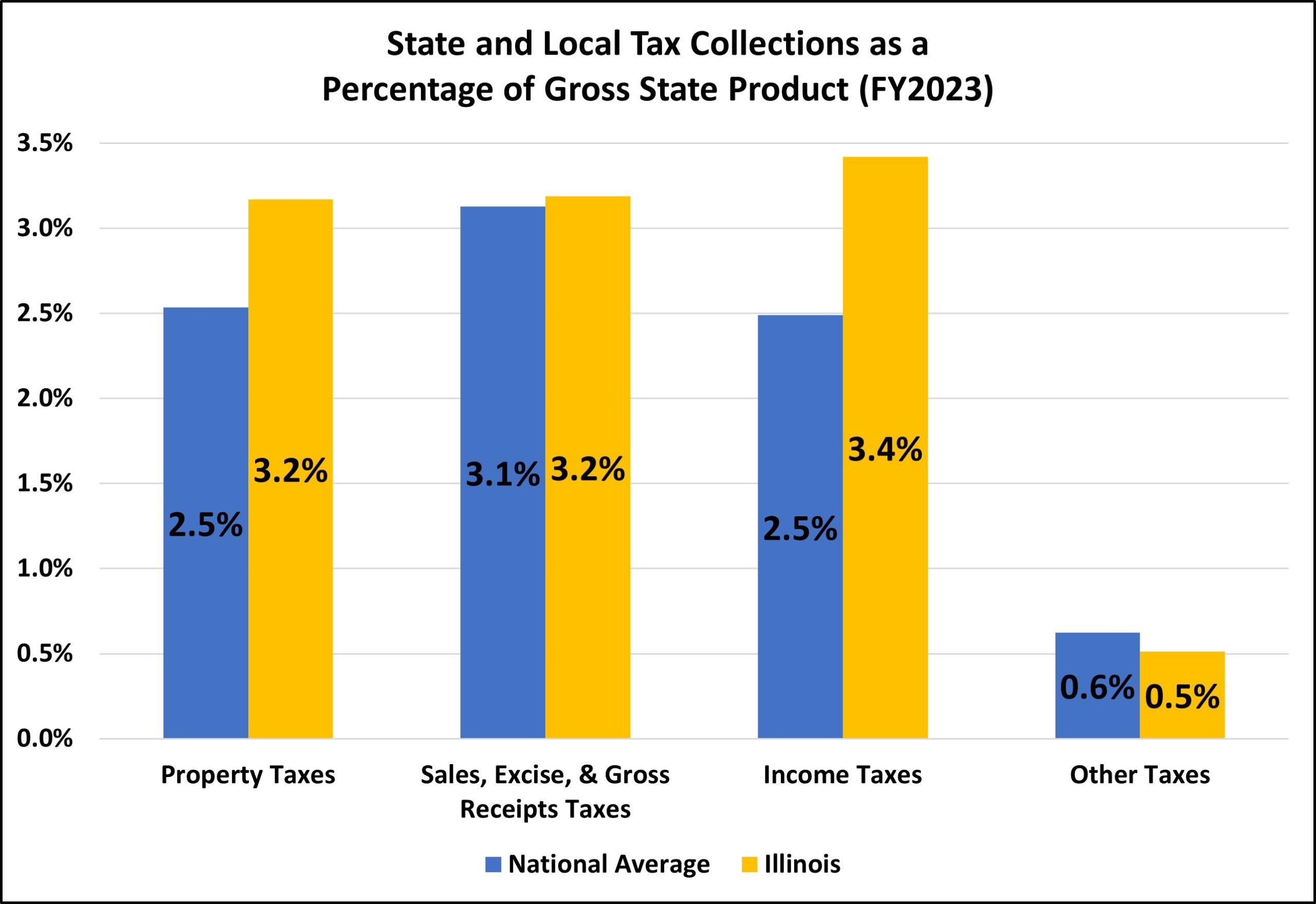

ILLINOIS’ MAJOR TAXES ABOVE THE NATIONAL AVERAGES

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Illinois state and local tax collections exceed the national average in nearly every category defined by the U.S. Census Bureau except “Other Taxes” which includes severance taxes, estate taxes, transfer taxes, and other miscellaneous taxes. While Illinois’ “Sales, Excise, and Gross Receipts Taxes” are only slightly above the national average, the state’s “Property Taxes” are about 25% above the national average, and “Income Taxes” are roughly 36% higher.

A significant reason for the large gap between the national average and Illinois on income taxes is the state’s unusually heavy reliance on business income taxes. Corporations operating in Illinois pay the Corporate Income Tax and all business types pay the Personal Property Replacement Income Tax.

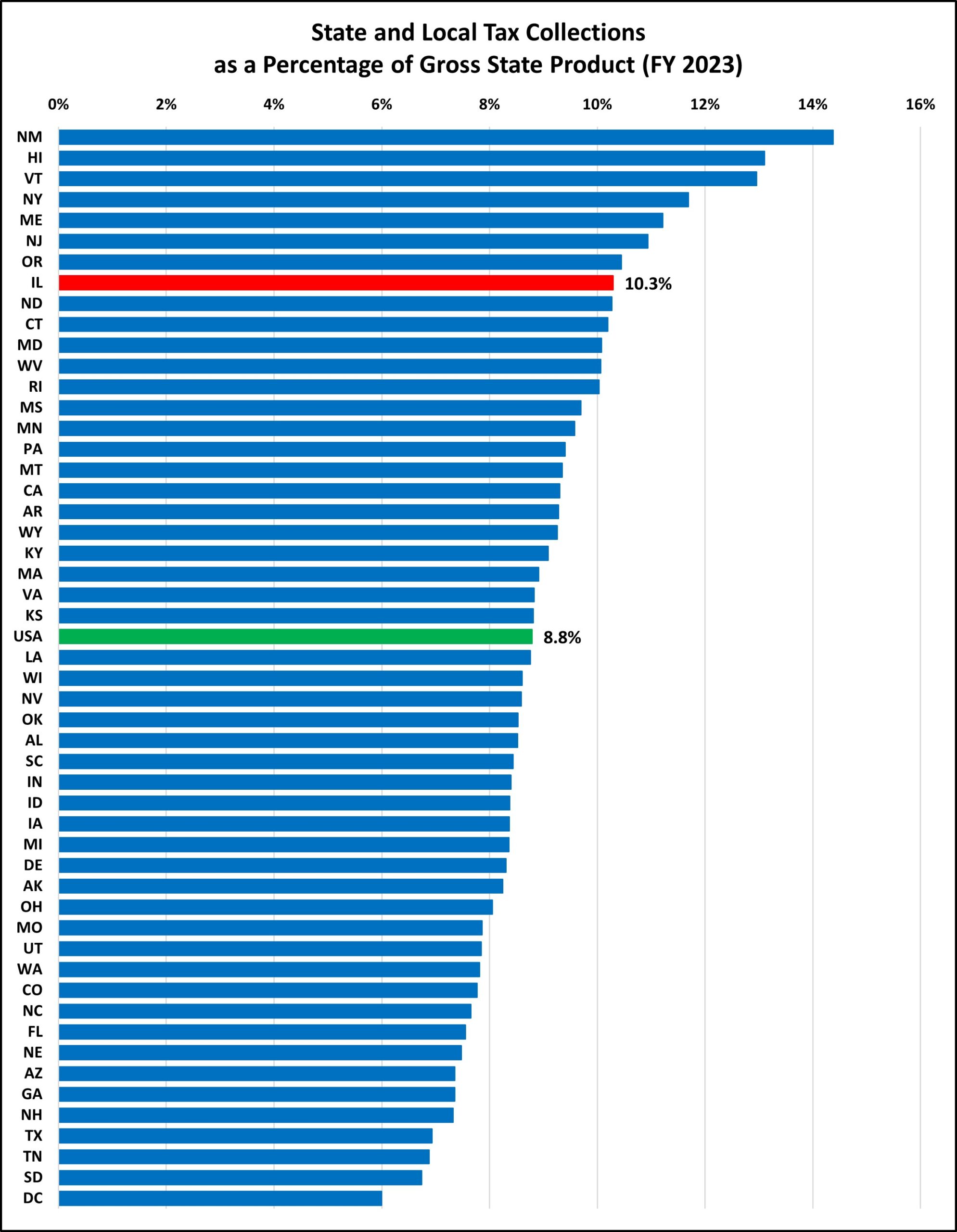

TAXES IN ILLINOIS ARE ABOVE THE NATIONAL AVERAGE

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

In FY 2023, Illinois had the 8th highest total state and local tax collections when measured as a percentage of GSP, at 10.3%. This is 17% above the national average. Illinois governments collected nearly $110 billion in taxes, or $16 billion more than what they would have collected if state and local tax structures were more in-line with the national average.

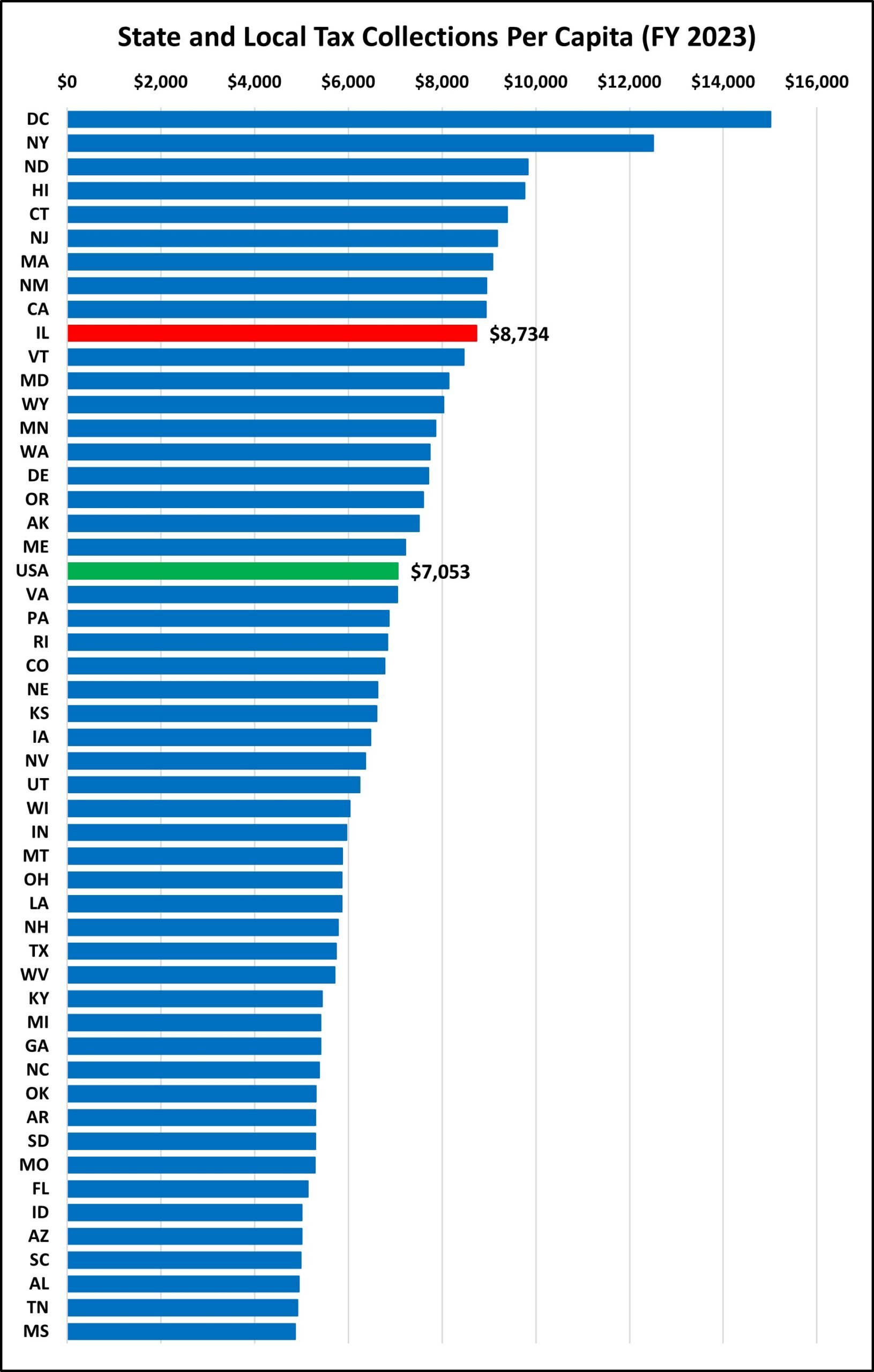

PER CAPITA TAXES IN ILLINOIS ARE HIGH

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Although per capita measurements fail to consider the states’ different economies, they still have a story to tell. When we say Illinois’ state and local taxes are 10.3% of GSP, most people will gloss over the figure as it’s essentially a foreign language. Saying that Illinois’ state and local tax burden is $8,734 per person, on the other hand, it is easier to understand (even though few people would pay this exact amount). The national average per capita state and local tax collection is $7,053. The national average decreased by $56 from the previous year, whereas Illinois saw an increase of $95.

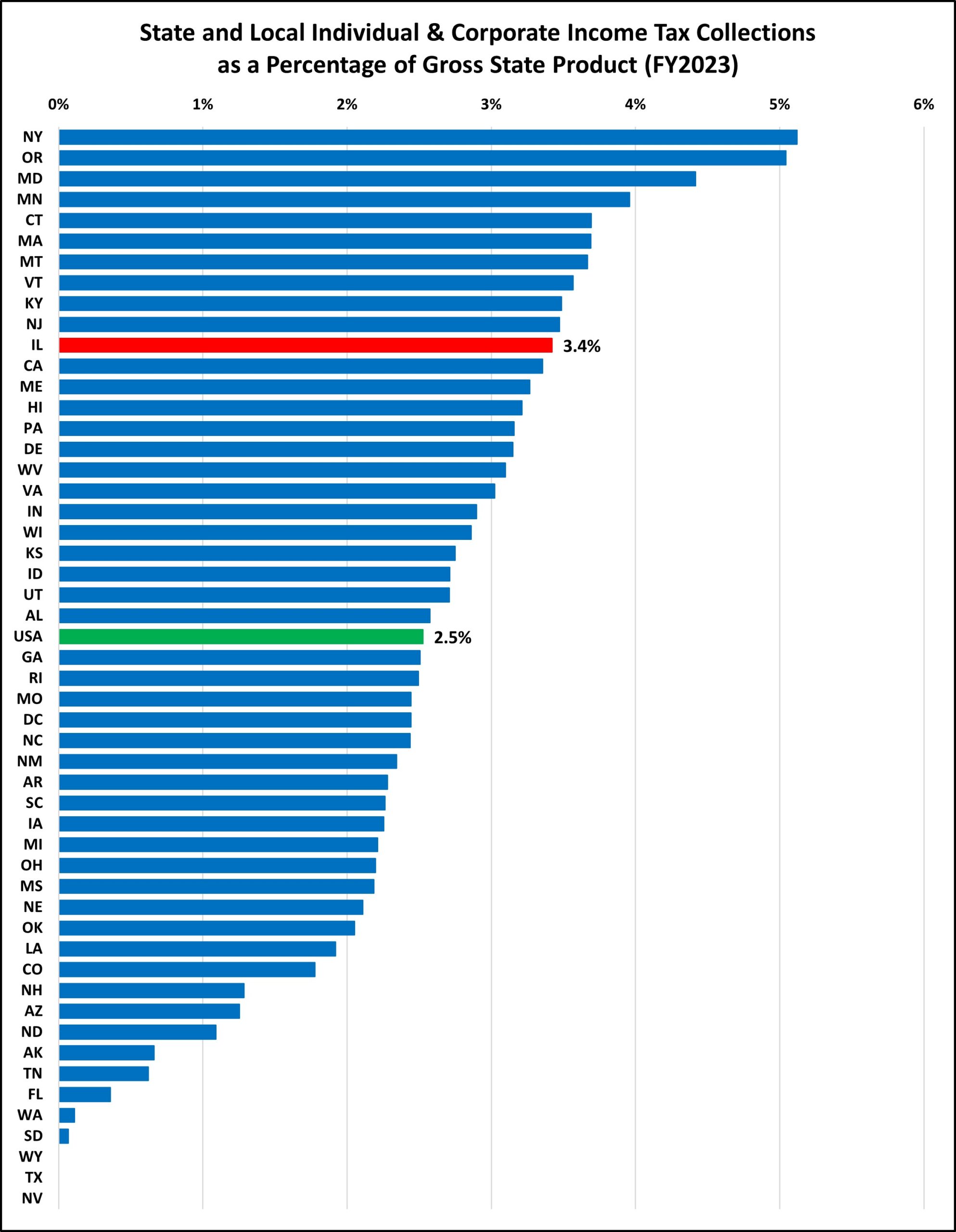

ILLINOIS INCOME TAX COLLECTIONS ABOVE AVERAGE

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Measured as a share of GSP, Illinois’ combined individual and corporate income tax collections are at 3.4%, or 36% above the national average. This underscores how Illinois leans more heavily on income-based taxes than most other states.

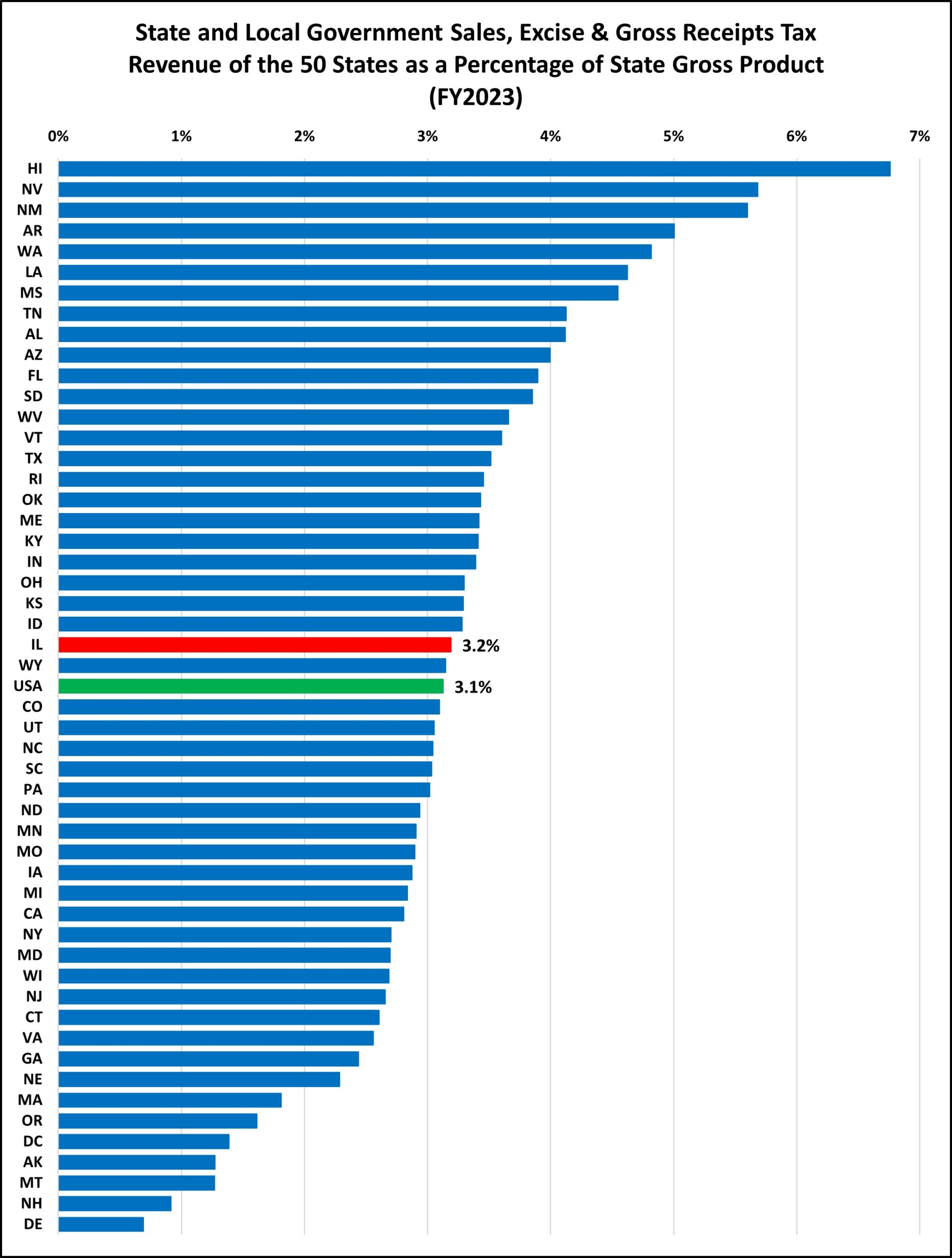

ILLINOIS SALES, EXCISE, AND GROSS RECEIPTS TAXES NEAR NATIONAL AVERAGE

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Although Illinois has one of the higher combined state and local sales tax rates in the country, its overall collections from sales, excise, and gross receipts taxes amount to 3.2% of its GSP – roughly the national average. This reflects the structure of Illinois’ sales tax base and highlights the importance of understanding Census classifications, which group traditional sales taxes together with gross receipts and excise taxes, inflating collections in states that rely heavily on gross receipts taxes.

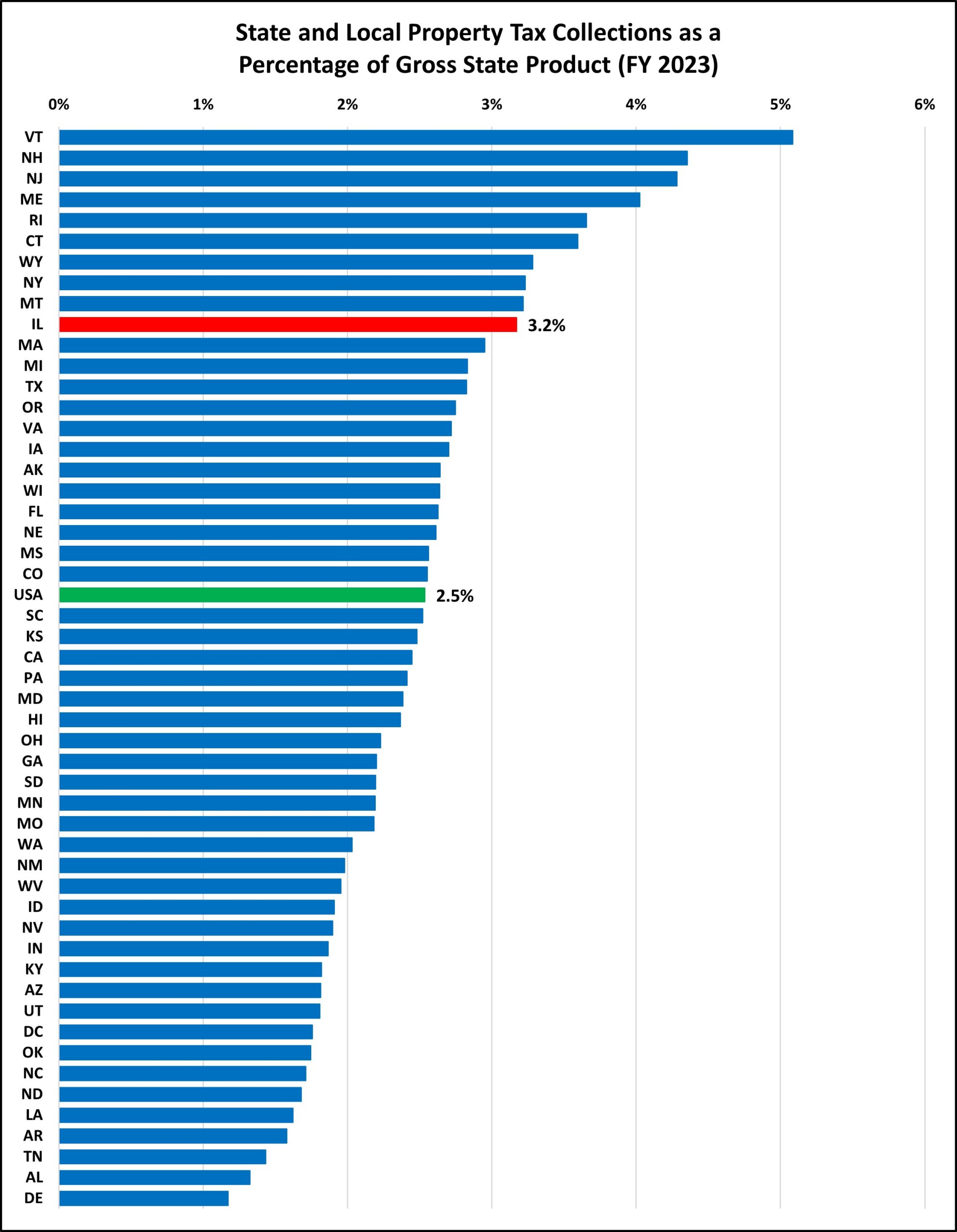

ILLINOIS PROPERTY TAXES HIGHER THAN AVERAGE

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, TFI Calculations

Illinois is often cited as the state with the highest effective residential property tax rate, yet total state and local property tax collections equal 3.2% of its GSP. While this share is well above the national average, it does not place Illinois among the highest states overall. Several states with higher property tax collections as a share of economic activity rely more heavily on property taxes because they do not levy a general sales tax or a broad-based income tax. Most states also tax personal property, which Illinois does not. As a result, Illinois’ aggregate property tax collections fall below the top tier even though many homeowners experience relatively high property tax burdens.

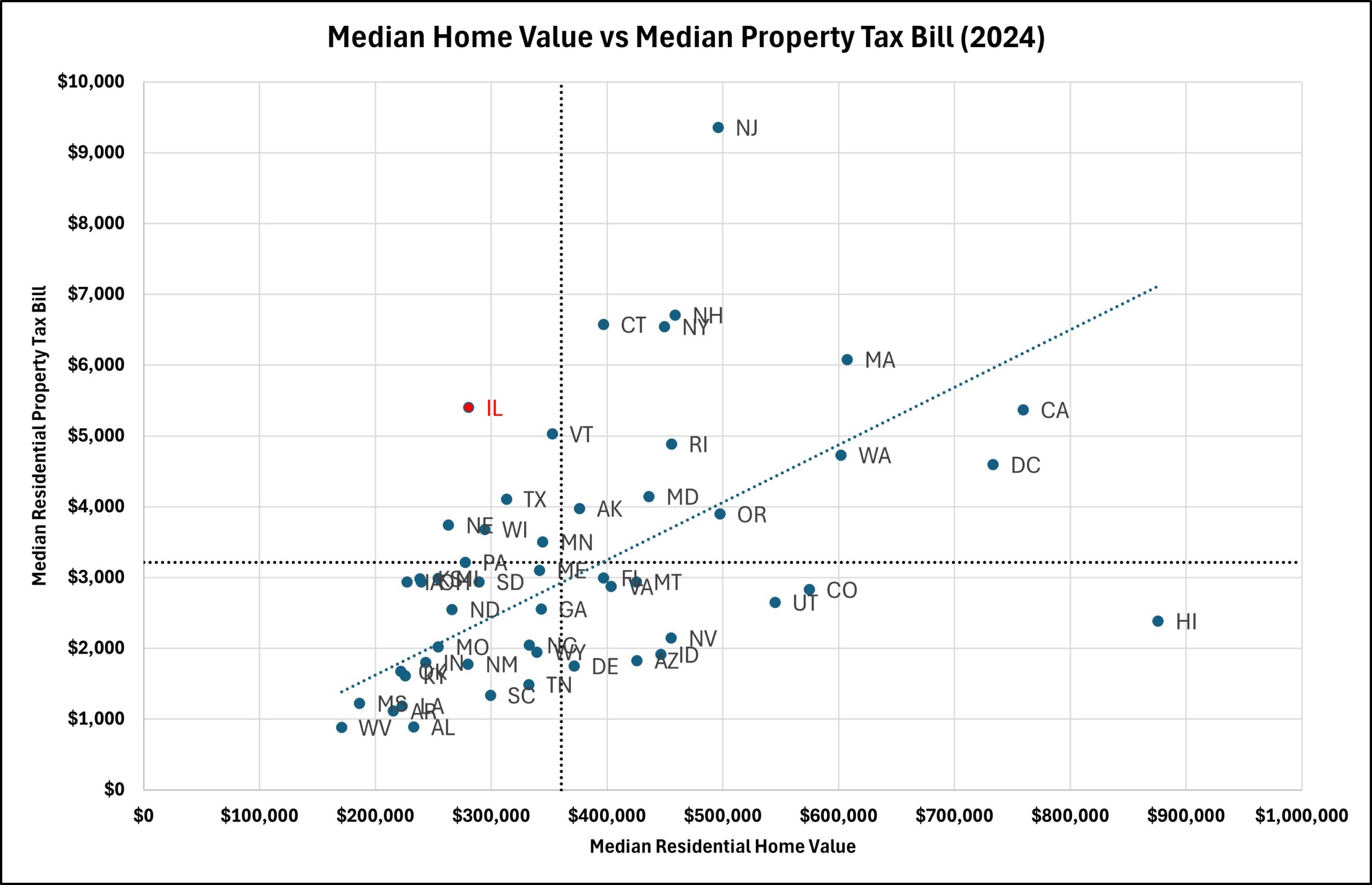

BELOW-AVERAGE RESIDENTIAL REAL PROPERTY VALUES INFLUENCE HIGHER PROPERTY TAX RATES IN ILLINOIS

Data Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2024 American Community Survey

Illinois is often cited as having the highest effective residential property tax rate in the country, but this chart reveals the two factors driving that ranking. On the vertical axis, Illinois ranks 6th highest in median property tax bills. Conversely, on the horizontal axis, the state ranks 34th in median home values. This combination of high tax bills applied to relatively affordable home values, mathematically results in the nation’s highest effective rate. The wide dispersion across the chart highlights how much states vary in their tax structures and their reliance on property taxes to fund local services. Ultimately, the data shows that while Illinois homes remain affordable, the tax burden on those homeowners is exceptionally high. Quadrants are defined using the national median residential home value and median property tax bill.

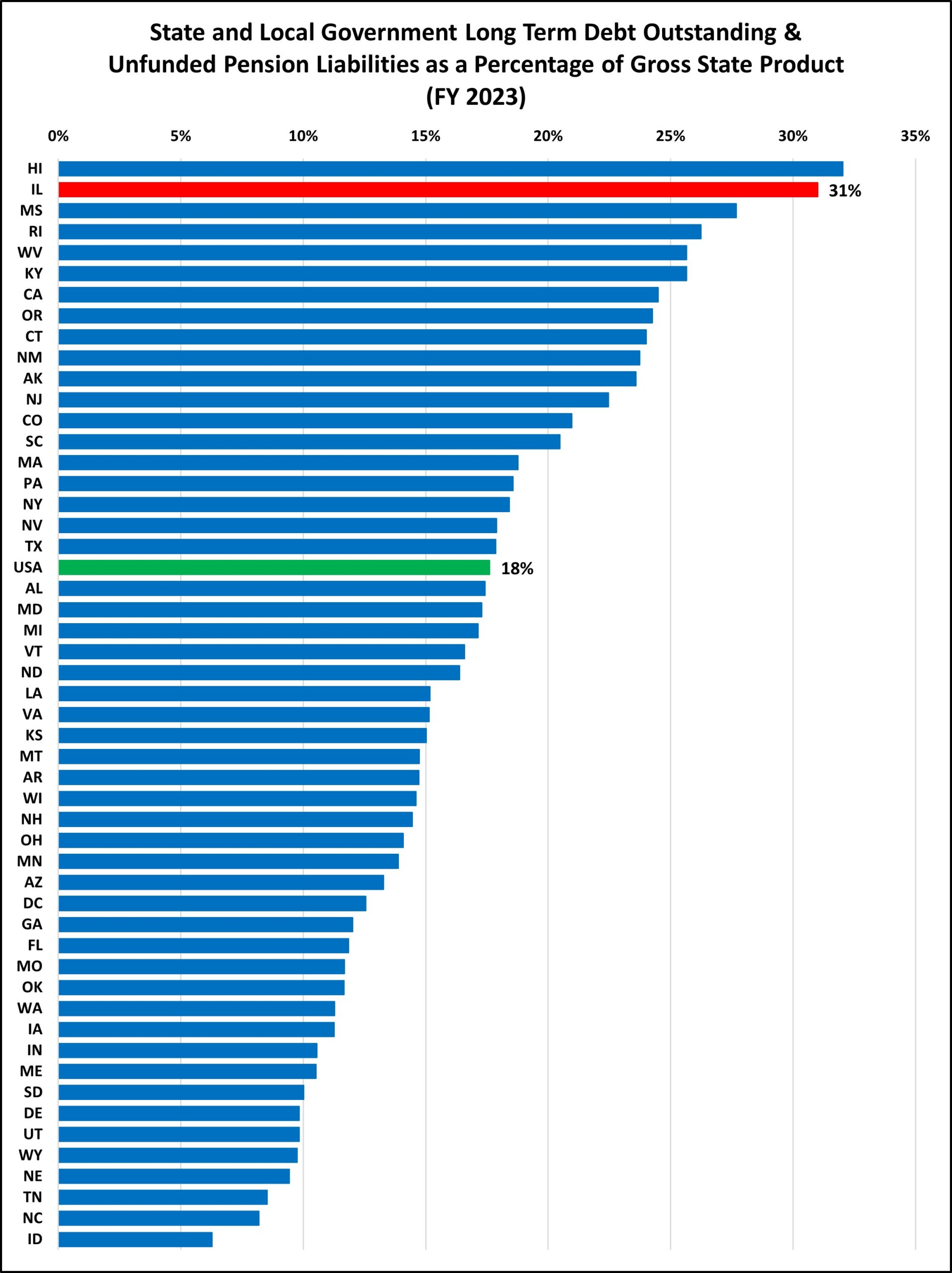

ILLINOIS’ DEBT AND PENSION OBLIGATIONS STAND WELL ABOVE THE NATIONAL AVERAGE

Data Source: “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” U.S. Census Bureau; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, and Public Plans Database, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, TFI Calculations

State and local long-term debt and unfunded pension liabilities represent claims on future economic output. Measuring these obligations relative to state economic output provides context for their scale and sustainability. Illinois stands well above the national average, reflecting both historically high levels of borrowing and the cumulative effects of decades of pension underfunding to support a mix of additional government services without raising taxes. Servicing these obligations in Illinois places ongoing pressure on state and local budgets, requiring higher taxes, reduced flexibility in funding public services, or both.